The first tarpon I ever saw was also the biggest. It appeared out of nowhere.

It was 2012, Charlotte Harbor. I was twenty-two, a few months out of college, and still actively evading the question of what to do with my life. I’d flown out on a whim to visit some friends, packing a borrowed 10-weight, full of hope and devoid of experience. We were slated to chase redfish and snook, but on day two, our guide pointed the bow of the skiff south, toward a deep, sandy flat on the windward side of a mangrove-choked island.

“We’re going after tarpon,” he said. “I don’t care what you guys want to do.”

The fish slid into view from over my left shoulder, broad, slow, prehistoric. It looked like a 200-pound punching bag with fins. Our guide’s voice dropped to a whisper I still remember.

“Forty feet, one o’clock.”

I cast. And I missed. Badly. My line tangled around my feet as I tried to regather for another attempt. The fish vanished, and the moment passed with it. No fanfare. No second chances. Just the sound of water against fiberglass and the sudden weight of what I somehow knew would become a lifelong obsession.

My cohorts consoled me, plainly conveying that I “wanted nothing to do with a fish that size.”

I wrote about that moment after the trip in a way only someone in their early twenties could. It was earnest, rambling, and overwrought. 'I didn’t want nothing to do with that fish. I wanted EVERYTHING to do with it,' I wrote. And that’s held true. For more than twelve years, I’ve carried that encounter, and the days that surrounded it, like a coin in my pocket, its familiar lines and pockmarks worn smooth, but never forgotten.

More than a decade and several return trips later, I was rushing through Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, bound for a connecting flight to Miami. I thumbed anxiously at my coin, the memory of that first fish and the others that had eluded me since. As I approached the gate, I noticed a figure crouched near the belt barrier marking the boarding lane. He was muttering in hushed tones about cap rates and cash flow, but his Wind River Roll-Top backpack gave him away.

Matt, part of our crew, had been making last-minute calls, trying to slip out of the corporate world without setting off alarms. By the time we boarded, we were already deep in conversation about the old debts we hoped to settle with these fish.

Outside baggage claim, we were met by Will, Peter, and a wall of heat. The Florida humidity hits you like it has a point to make. Before we even reached the car, we were peeling off layers of fleece and pulling on board shorts and sandals. Then, we hit the road.

There’s something transformative about the drive down Route 1. It’s not just scenic. The road narrows, the water encroaches, and the noise of Miami-Dade starts to bleed away. We dropped south through the Everglades, past the mangroves of Biscayne, into that sun-baked coral archipelago where Florida runs out of land and keeps going anyway.

Crossing the Whale Harbor Bridge into Islamorada felt like arriving somewhere mythic. The sun was just beginning to dip, throwing long shadows across trailered boats and cracked pavement. The air smelled of salt and diesel, and something sunbaked and stubborn. It wasn’t beautiful in the way postcards promise. It was better.

I was no longer racing to check a fish off a list. That urgency had faded, not because the dream was any smaller, but because the place and the people who call it home had grown larger in my heart. With each return to Florida, the mission felt less like unfinished business and more like a pull toward a feeling, a way of moving through the world that asks you to slow down and take notice. A world shaped not just by its natural beauty, but by its people.

The legends here aren’t just stories. They’re standing on the poling platform behind you, watching your cast unravel in the wind, and wondering why you didn’t spend more time practicing in the park before you brought it on their boat.

In the Keys, the legends run deep. Sportfishing here has roots going back nearly a century, to the days when Zane Grey and Ted Williams traveled south chasing bonefish and tarpon on early bamboo rods. Guides like Bill Curtis and Jimmy Albright shaped the game before most people even knew it existed. The Florida Keys became the proving ground. The techniques, the boats, and the flies all of it evolved here. Among all those names, Tim and Robert Klein stand out. Not just for their skill, but for how completely they belong to this place.

I’d heard the name Klein long before this trip. In books and articles. In stories from friends and other guides who didn’t hand out compliments easily. Tim and Robert aren’t just accomplished. They’re revered for the authenticity of their experience here. Raised in Islamorada, sons of a shipwreck diver, they grew up sleeping on the decks of old boats, eating tinned sausages under the stars, and learning how to run a skiff as soon as they were old enough to ride bikes. If you spend enough time chasing fish in serious places, you learn who carries real weight. And the Kleins do.

They carry themselves with the same quiet seriousness they were raised with. They aren’t figureheads. They don’t advertise, and they certainly don’t broadcast their lives online. But if you spend enough time fishing in any corner of the globe, you’ll hear their names spoken with the kind of reverence reserved for people whose credit is good at any fishery on the planet.

We met Tim and Robert at the Lorelei each day just after first light. There’s a hum of anticipation there in the morning, even when the air is still, and the sunrise pushes a golden glow across Florida Bay. You could smell the fry oil heating up inside. Music played low behind the bar, drifting through tinny speakers.

The patio there is more than a waterfront bar. It’s a sanctuary, a bulletin board where the day’s events report themselves. On the left side of the entrance, a handful of tables sit, claimed not by signage but by tradition. No more than four or five in total. If you’re new, you learn quickly that those tables aren’t yours. Maybe someone will tell you. More likely, you figure it out by watching, which is how most things work here. And if you hold your own out on the water, you might find a chair waiting for you when you return at the end of the day.

Below the patio, skiffs line the dock like thoroughbreds waiting for the post horn to sound. Each guide sits at their center console, peeling fluorocarbon from tippet spools, checking knots, scanning the mouth of the marina with a kind of restless energy. No one says where they’re going, and everyone wants to get there first.

That first morning, Robert Klein greeted me and Will with the bright energy of someone who knows the odds and still chooses optimism. We didn’t talk about fish, or weather, or goals. We talked Florida Panthers. Yeah, South Florida’s NHL team. Because when you're steeling yourself for the excitement and heartbreak of tarpon fishing, it’s easier to focus on something unrelated. Something safely disconnected. Anything but the skills you’ll soon be putting on display. It was Schrödinger’s cast. As long as no one asked, no one had to know how bad it was. Robert didn’t need to address my crisis of confidence yet. The pressure was still theoretical. And for about 45 more minutes, he would remain blissfully unaware.

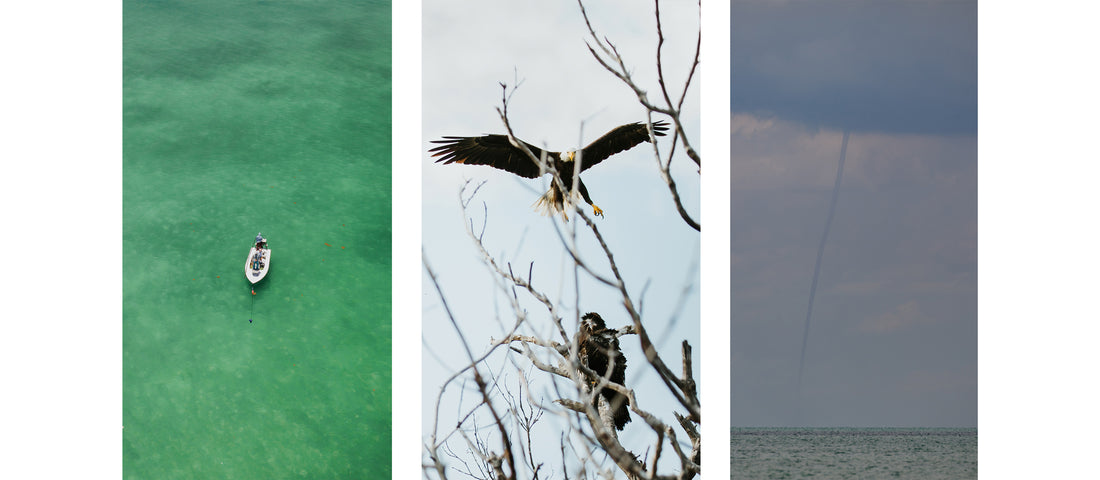

Moments later, Robert turned the key and we idled north, out of the marina and into the backcountry of Florida Bay. The oceanside to the south gets most of the attention. Its exposure to travel lanes, expansive sight lines, and shots at migrating fish attracts anglers from around the world. But the real heart of this place is in the backcountry, in the tangled maze of islands and flats where the landscape contrasts against the sky. The environment here is dynamic in a way that would take a lifetime to understand. Shallow runs of turtle grass. Cut channels lined with sponge. Mangrove islands blanketed by a cacophony of calls and squawks from resident and migratory birds. The occasional depression that hides the wreckage of a downed drug runner or a wayward vessel.

We swapped stories, light and loose. Local watering holes. Old friends. Glory days. Tangents that wandered. Every so often, the conversation snapped shut when a fish slid into view. Robert gave me plenty of opportunities that day. I blew every one of them.

There’s a method to the madness. You run, you pole, you scan, you wait. The pursuit provides, even when you come up short. With each unsuccessful lap across the flats, anticipation accumulates. Not the cheap kind that fades when you leave, but the kind that precedes something important. Something that will change the way you see the world.

We didn’t come tight that day, but it didn’t feel like a loss. By the time we pulled back into the dock at the Lorelei, it had settled into a kind of calm clarity. The day had left something open and unfinished in a way I’ve become quite familiar with over the years. I sensed that I was moving closer to what was that I was chasing. Not just the fish, but the feeling. I found myself reaching for that old coin of a memory again, not for luck, but to remind myself it was never just about the fish.

That night, I sat by the beach, listening to the sounds of waves crashing, the drone of airplanes overhead, and boats offshore. I pulled up my old journal from Charlotte Harbor. I read the lines I’d written at twenty-two: 'That fish made my knees go weak. I forgot how to breathe. I’ve never seen something so big move that quietly.'

Back then, I obsessed over that one fish.

Now, I come back for what the pursuit shows me. For how it reshapes the way I move through the world. The next day, I’d get another shot, with a different Klein manning the platform behind me.

The second morning, Peter and I stepped, bleary-eyed, onto Tim Klein’s skiff.

We pushed off from the Lorelei, idled out of the marina, trimmed up, and hammered down. If you remain stubbornly focused on tangling with a trophy tarpon oceanside, you’ll miss the real gift of fishing with guys like Tim. It's the chance to understand what keeps them here, not just what brought you.

That was the plan that morning. We told Tim we wanted to see some of the places that shaped him into who he is today. Flats where your reputation is earned through effort, not social media attention. Tim’s tournament résumé as a guide is world-renowned. But among the initiated, he’s best known for something quieter. His relentless pursuit of bonefish and an almost uncanny understanding of their patterns, habits, and moods.

Tim didn’t say much as we picked through narrow channels and traversed expansive lanes between islands. The occasional adjustment to the throttle, the angle of the boat, the direction of his gaze. Guides like these see things we don’t. That’s the draw. To fish with someone who’s been in a place so long that they don’t just recognize the water. They anticipate what it’s prepared to reveal.

We approached a turtlegrass flat that looked, to me, like every other, but Tim trimmed down and came off plane. We had arrived at a nameless location that had once been one of his most productive bonefish spots. Peter climbed onto the casting platform while I stretched my arms and took in the scene. The light came in low and slantwise, catching the tops of distant mangroves with a painter’s touch. Tim stood behind me, poling us quietly onto a flat he’d known since he was a kid. These weren’t just spots on a map. They were landmarks in the story of his life.

Tim and Robert grew up just a few blocks from where we launched that morning. They learned these waters in a leaky Boston Whaler with a Johnson 50 that was just as likely to strand them as it was to start. They’d run it until it gave out, then plead with their dad on the VHF to come tow them home. Captain Bob Klein had been a marine patrol officer, then a treasure diver, chasing ballast stones and pieces of eight from Spanish galleons scattered along the reef between Key Largo and Islamorada. He kept a dive shop at Ocean Reef in the seventies, and his boys spent their childhoods sleeping on the decks of sun-bleached boats, fishing under the stars, and sneaking out until dawn. By the time Tim and Robert were teenagers, boats weren’t just for fishing. They were for living. For transportation. For freedom. School mornings started at the dock down the street from their home, and ended there, too. Skipping class altogether to head due north into the backcountry.

Their mentors were legends, though they didn’t know it at the time. Names like Jack Brothers, Steve Huff, Harry Spear, and Flip Pallot. These were men who didn’t offer praise easily, and never twice. But the Kleins didn’t just look up to them. They grew up around them. Jack gave Tim his first real shot at tournament guiding. Before that, he covered some of Tim’s early costs, making it clear the gesture wasn’t a gift. It was a test. Steve offered quiet insights and hard-earned lessons in patience and discretion.

The way of doing things in the Keys isn’t posted. It’s handed down, mostly by example. If you moved quietly, watched closely, and made yourself useful, you might get asked back. If not, the lesson ended there. Tim told me they learned by staying out of the way and paying attention, waiting quietly until someone decided they were worth the time. You didn’t speak unless you’d earned the right. You watched, tried, failed, and tried again. And if you hadn’t put in the work, the water wasn’t going to give you anything in return.

Growing up in the Keys wasn’t just about fishing. It was about picking up unwritten rules. Where to go. Who to listen to and when to stay quiet. It was about understanding that the right to be a steward of this place was earned through action, not desire. And that the right way to carry yourself doesn’t change, even when the world around you does.

As we drifted across the flat, Tim’s eyes traced a depression on the bottom I couldn’t see, scanning for signs of life.

He spoke of the changes he’d witnessed over the years. Not with bitterness, but with the quiet gravity of someone who understands that belonging here means more than knowing where the fish are. It means paying attention to what is slipping away and caring enough to fight for it, even when the fight is slow and uncertain. Many of the grass beds that once teemed with life have grown patchy and sparse. Water that used to run clear now turns murky after heavy rains. Pollution and development have choked off the natural flow of freshwater from the Everglades, changing salinity patterns across Florida Bay.

The challenges facing this fishery will still be here long after he is gone, but he speaks about them like someone who has made a pact with the place to protect what he can, for as long as he’s able.

“The thing that I’ve noticed is a salinity problem,” he said. “Florida Bay isn’t getting the freshwater it once did, and it shows. Over the last 45 years, I’ve watched that shift. Used to be bonefish all over the bay. There was a standard, and you knew what it was. Now, that standard has diminished.”

He pointed toward a flat in the distance that he remembered from his youth, a place that once held steady populations of bonefish and spiny lobster. “It used to be alive with grass. Now it's just sand and mud.” It wasn’t a rant. Just the weariness of someone who had been watching long enough to stop being surprised.

He explained how pollution from sugar cane processing and unchecked development had choked off the natural flow of freshwater from the Everglades. “We have all sorts of projects being developed to try to change outcomes down here,” he said. “It’s slow, but there’s hope.”

His hope wasn’t something he broadcast. It came from decades of proximity. From witnessing slow change and refusing to turn away. “This is what keeps me going,” he said. “It’s where I feel most at home. It’s what I know best.”

For Tim, guiding is more than a profession. It’s a form of stewardship. And now, the next generation is beginning to carry that forward. “They’re the greatest,” he said, speaking of the young guides now entering the fishery. Many, including his son, are showing up early, staying informed, and getting involved. He spoke of organizations like the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, working tirelessly to research and advocate for these waters. Their efforts to identify bonefish spawning sites and protect critical habitats are steps in the right direction. “They’ve got the right mindset. They don’t want to lose what makes this place so special. They want to protect the way of life that comes with it.” The work is ongoing. Imperfect. Slow. But it’s happening. The pace may frustrate some. But for the ones who know this water and still choose to show up, it’s a pursuit worth continuing.

We fished hard that day. The chances came, and I missed all of them, as is customary. I wasn’t remotely discouraged at this point, just in wonder at another installment in the long-running saga of trying and failing to connect with these fish. I didn’t seal the deal, but I came close enough to keep me hopeful, and far enough to keep me honest.

We pulled back into the Lorelei, sweaty, tired, and more than a little pickled. We shuffled up to the bar and ordered whatever frozen concoction was spinning in the drink maker, calling for ice-cold rum and sugar to take the edge off. That’s the unspoken math of chasing tarpon here. How many blown chances can you endure before a drink starts to feel like the only honest response?

By the time we found seats on the patio, the rest of our party had materialized. Robert, Will, Matt, a couple of other guides who’d been out that day. We didn’t return triumphant, but we’d left enough of ourselves out on the water to earn a place at the table. The banter was soft and off-angle, the kind that doesn’t need a point at all. Just enough to round out the edges of the day.

That night, we sat on the beach again, gazing out into the inky darkness of the ocean and paving over memories of missed opportunity with aged cigars I’d hidden away in the back of my humidor for moments exactly like this. Some of them were nearly as old as my pursuit of this fish. As tendrils of toasted Cuban black leaf drifted away on the wind, I found myself thinking again about Charlotte Harbor. I’d revisited that trip many times over the years, usually with a mix of embarrassment and nostalgia. Reflecting on it again, robusto in hand, it felt less like looking back and more like checking in on an earlier version of myself.

Back then, I was convinced that fooling the silver king would answer something. What mattered to me now had been stretched wide and softened over time. The fish I sought was still out there somewhere. It still pulled at me, but more as a compass heading than a destination. Something to aim toward, not arrive at. Even so, I watched the dark, turbulent water in front of me for signs of life, until all that remained of my cigar was a hot, smoldering nub. Just in case.

The next morning, Matt and I were back on Robert’s boat. The breeze hadn’t picked up yet. Visibility was excellent. Everything still felt possible.

There’s something easy in the way guys like Robert and Tim move with a push pole in their hands. No performance. Just the quiet choreography of a seasoned guide who knows better than to waste effort. We eased into the day, trading familiar jabs about my comically bad luck. My long, slow, and notably fruitless quest for this fish had become something of a running joke. The water where we dropped the sea anchor was slick, almost too still, but Robert liked the look of it. “We’ll get a good shot here,” he said. “We just need to be patient.”

We stood watch like statues, waves of heat rippling off the water and distorting the horizon. Up front, I was scanning, processing, and repeatedly checking the coils of line below me on the deck. Matt stood next to me, doubling my effort, having broken the seal on his Tarpon journey many years before I had, and plenty of times since then. Then, without any fanfare, three fish appeared, pushing straight toward us. A string, tight and slow. Only the occasional silver flash betrayed their location, direction, and speed, glinting like shipwrecked coins, tumbling along the ocean floor toward us.

Robert didn’t raise his voice. He had grown familiar with my program. By this point in the week, he no longer harbored any reasonable expectation of success. I’d been slowly cultivating in him a resigned tolerance for my inability to close the deal.

“Coming in at one o’clock. Easy. Easyyy…”

“Got it.”

The fish closed to 80 feet, then 70. I readied myself with a familiar sequence of false casts. 60. The fish were tracking directly toward us, and it was looking increasingly unlikely that I was going to be able to pass off another missed opportunity on wind, lockjawed fish, or a whole host of other excuses I had availed myself of over the past few days.

“Drop it," Robert whispered, as they approached within 50 feet.

My old words echoed in my head. ‘That fish made my knees go weak. I forgot how to breathe.’

The fly landed softly, 10 feet off the nose of the lead fish, and I began stripping line back toward my feet.

One slow strip. Then another.

At thirty feet, the lead fish tipped slightly. I teased the fly back to the boat with short, rapid strips, frantically gathering line, just far enough ahead of its nose to keep it curious.

Twenty.

The two trailers peeled off with urgency, pushing south and away when they’d changed their minds. But the lead fish stayed locked in, steady and sure, still closing.

Fifteen feet.

The fish twitched, pinning its fins down, and surged forward. I watched the mouth snap open, wide and deliberate, engulfing my baitfish imitation. The sound was like someone ripping a bed sheet underwater. The whole fish rolled, silver scales shining like a signal flare.

The take unfolded in slow motion. The explosion that followed did not.

I set with everything I had. Once. Twice. And the hook found purchase.

The water detonated below me. A cannonball of muscle and chrome cleared the surface, head shaking, mouth open wide enough to swallow a propane tank. Its gill plates rattled as it arced through the air, then crashed back down with a thunderclap and bolted off the bow.

The take had happened so close I could see the gold and pewter of the fish’s left eye as I hopped a jig, trying to clear the line from underfoot. Somehow, the coils unfurled clean, the line sizzling through oversized guides, out the tip of the rod, and off into the Atlantic.

Robert and Matt erupted behind me. No holding back now. Full-volume celebration. They knew how long I had been looking for this fish.

“Yeah! That’s it! That’s the one,” Matt shouted.

The silver king tore across the flat like it was dragging a loose kite string, carving a frothy scar through the shallows. The reel was screaming, line cutting a sharp wake, and for a while, it felt like I’d hooked the bumper of a car that just barely realized I was there.

Then, it launched again. Full-bodied and vertical, into the morning light. Every inch of it was visible, from shoulders to gills to tail. It hung there for a beat, then came down like a wrecking ball. It was the kind of sight that doesn’t just lodge in memory, but recalibrates something. A private, searing reminder of what it means to be fully alive.

The next ten minutes were a blur of chaos and instinct. The fish ran hard, then deeper, pulling us across the flat and into open water. Robert stayed calm, adjusting the angle of the boat with the push pole. Matt stood behind me, whispering wisdom.

I bent my knees and stayed low, letting the rod and reel do their job. I took a breath only when I remembered to. The fish lived up to the reputation I had built for it. It peeled line in long, violent bursts, turning hard every time I gained anything back.

After what felt like forever, it began to slow. Circling wide around the perimeter of the skiff.

“That’s a good fish,” Robert said. “Take your time.”

I brought it closer. Leader to the top guide. Then I saw it, truly saw it, for the first time. Laid out just below the surface, broad-shouldered and bright, gills pulsing, its blue-green back catching the morning light like oxidized copper.

I leaned over the gunwale and slipped a hand around the wrist of its tail. I reached with my right hand to free the fly that had come to rest in the bottom corner of its mouth. It hovered for a second beside the boat, then kicked. Once, dismissively, and hard. And disappeared into the distance.

I crumpled to the deck of the skiff, breathless and laughing like a maniac. Robert cracked a grin and handed me an ice-cold beer.

“You alright?” Robert asked earnestly.

“Yeah,” I said, not even convincing myself. The weight of the journey to intercept one of these fish, mixed with adrenaline, lactic acid, and oppressive heat, combined to form a powerful brew. I wasn’t alright. I was wrecked, elated, riding the kind of high that scrambles your ability to speak in full sentences. It wasn’t the end of the journey I started all those years ago. Just a reminder that belonging here comes slowly, by taking the long way in.

Back at the dock, the buzz was different. I couldn’t tell if it was the fish, the fatigue, or something more elusive settling in. Robert leaned against the console, looping leader between his fingers. Tim wandered over, arms folded, sunglasses pushed high on his forehead.

“Got him,” he said, not asking.

I nodded. Still gathering my composure.

We fished the rest of that day and all of the next, but everything after that fish quieted, the tension draining out of the trip. I moved slower. Cast less. Paid more attention. I had nothing left to prove. I just wanted to be present. I fished like someone trying to remember the place, not just where the fish held, but how the wind sounded in the mangroves and how the sun shifted across the flat. I wanted to carry enough of it home to make the feeling last.

My experience that day hadn’t ended the search. It had simply changed its shape. What once felt like a finish line now felt more like a threshold. It was an invitation to engage with this place no longer as a visitor chasing a moment, but as a student of its habits, still learning the language.

That evening, the crew thinned out. Matt, Peter, and Will had to catch flights, the way visiting anglers always do. Straight off the skiff, into a rental car, headed north with salt still behind their ears. I stuck around. Before long, I was back at the Lorelei, in the same corner of the patio where I’d sat all week, only this time with no nerves and nothing to chase. A cold drink in my hand, water lapping against the dock pilings, and Tim and Robert sitting across from me, steady and familiar in their element. The kind of fixtures that held everything together.

We avoided the fish talk. Just local politics, boat repairs, and the Florida Panthers. The kind of small talk that makes you feel like you belong. That’s the thing about fishing with people like them. The real gift isn’t the spots or the shots. It’s how they make you feel like part of the fabric. Not just someone passing through, but someone the place seems to recognize. Maybe only a little, and only for a while. But in a way that stays with you.

It’s a funny thing, watching strangers turn into familiar faces. I hadn’t known Matt or Peter before the trip. Everyone brought their own reasons, their own ghosts. Tarpon just have a way of dragging something honest into the open. When someone sees the shape of your obsession up close, when the thoughtful cast, the endless enthusiasm, and the genuine heartbreak are on full display, it stops being abstract. You see not just the effort, but the reason behind it.

That exposure doesn’t just bind you to the people in the boat beside you. It binds you to the ones on the platform too. Guides like Tim and Robert don’t just watch you fish. They witness the full arc of your experience. The nerves. The misses. The moments you doubt yourself. And if you’re lucky, they meet that vulnerability with care. Not in words, but in effort. In the way they keep showing up. That’s the real connection. Not to the fish, but to the people who make room for your honest self on their water.

That feeling isn’t earned in a week. It doesn’t come with a fish. It comes slowly, if at all. It’s built by the people who live in rhythm with the water. People who fish through the bad years. Who show up. Who teach. Who give a damn.

People like Tim and Robert.

I don’t pretend I’ll ever belong to the Keys like they do. That kind of belonging isn’t something you visit into being. It’s earned slowly, the way Tim and Robert learned when they were kids. You show up early. You stay quiet. You watch closely. And if you keep doing that, you start to understand what matters. Not just where the fish are, but how people carry themselves. What they choose to pass on.

Maybe I’ll never fully belong. But I’ll keep coming back. I’ll keep trying to be useful. And I’ll aim to leave a little less behind each time I go. That’s all the coin was ever meant to be. Not a debt to settle, but a reminder to keep going. To take the long way in, every time.

The pursuit of bonefish and tarpon stretches far beyond the Keys. Across the coastal waters of the southeastern U.S., the Gulf, and the Caribbean, these fisheries face growing challenges. Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is doing critical work to protect them through science, education, and advocacy. If you're getting ready for your own trip, take a look at our saltwater collection and our Fishpond x BTT products, designed to support both the journey and the resource.